Organizations depend on increasing their innovation capabilities — specifically, deepening their talent benches with people who can think critically and originally to solve problems and develop new solutions. But when the majority of a workforce is not engaged or disengaged, business performance and profits shrink. The cost of underutilized human assets can run from the tens into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Without a fully engaged and high-performing workforce, firms simply cannot grow and thrive. What can companies do to turn things around?

Sources of Employee Disengagement

Human capital (HC) is often the largest expenditure and, for knowledge-based organizations, the most important contributor to both bottom and top line revenues. Traditionally, firms manage human capital by attempting to improve performance (through training and talent management), trying to ramp up productivity (asking employees to work longer and harder); or shrinking costs (lowering healthcare benefits, managing turnover, “right-sizing,” and so on). Despite taking such measures, an enormous number of forces are undermining the ability of employees to perform at their best.

On a macro level, the current state of the economy and rapid technological and social changes contribute to employee stress. As the business demands more productivity from knowledge workers, employees suffer in their personal lives. They spend less time doing things that restore their energy — engaging in family, friends, hobbies, physical exercise, or even sleeping. Yet, over the last decade, energy has been defined as the fundamental currency of high performance. Individual, team and organizational performance are grounded in the skillful management of energy. However, organizations have often isolated their training curriculum by focusing on improving an individual’s productivity versus addressing and integrating the management of energy so that their teams and organization can excel.

As an example, let’s examine how psychological issues are manifested. Nearly 1 in 3 American women categorized their stress levels as extreme in 2008. In addition, 69% of respondents felt that a mental health professional could help them in managing their stress, although only 7% of the respondents actually availed themselves of these services. When employees are unable to manage their stress at work, they often exhibit negative behaviors such as impatience, uncooperative behavior, defensiveness, hyper critical thinking and pessimism. All these emotions negatively affect teams and decrease individual and collective ability to perform. In attempting to cope with stress, employees may resort to efficient albeit unhealthy “decompression” strategies that provide immediate, but unhealthy, gratification (resorting to too much television, alcohol, comfort foods, recreational drugs, mindless activities—web surfing, video games, and so on).

These combined stressors contribute to what is known in the field of health and productivity management as “productivity impairment”. To date, productivity impairment has been measured by two key metrics “absenteeism” and “presenteeism” or the absence of the worker’s active thought and engagement while he or she is physically on the job. Both metrics reflect a deficit of an employee’s physical and emotional health. While we believe that identifying these relative productivity deficits is important in order to deliver meaningful solutions to address them, productivity impairment tells only part of the story. To truly address employee productivity, employers need to move beyond the existing productivity impairment framework and expand it to a new “performance enhancement” model, based on a more holistic view of employee productivity and performance.

What would happen if employees not only met the thresholds found in the deficit model, but pushed through the ceiling of common expectations, even as they avoided disengagement or burn out? What if there was untapped or thwarted potential to be unleashed? Just like in the world of sports, we must ask: Are there business performance records still to be broken?

The Body is Business Relevant™

What does an engaged employee look like? She is emotionally resilient and under control in the face of a storm. She is attentive, focused, creative and able to solve problems. She processes information efficiently and effectively. Her eyes shine. She likes her work and, yes, she is very productive. Beneath the surface, she taps into sustained levels of glucose and oxygen, supplied through food and breathing, and sufficient sleep. Let’s take a closer look at the physiological effects of these prime performance drivers:

The role of nutrition

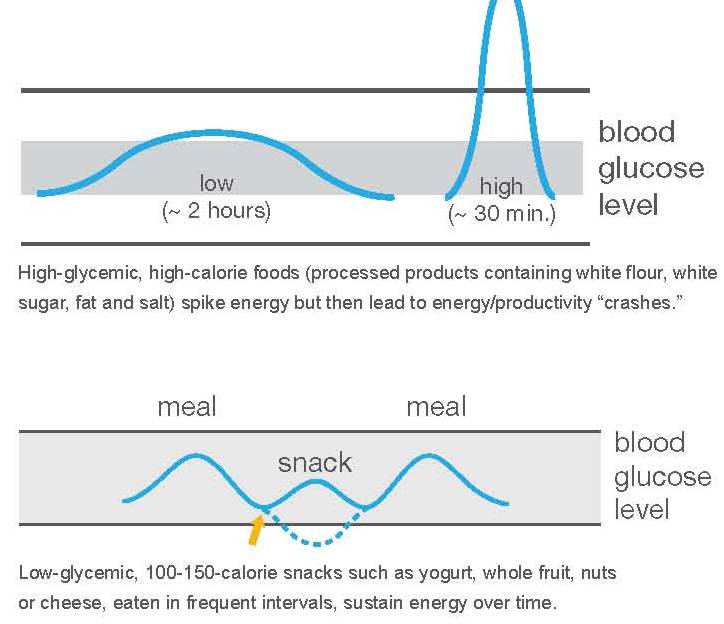

Eating the wrong kinds of food and not drinking enough water lowers workers’ ability to sustain energy and to think creatively.Unfortunately, too many employees skip breakfast, or reach for donuts and bagels. These kinds of high- glycemic foods cause a spike in blood glucose, and then retreat in 30 minutes or less, causing a feeling of hunger requiring something quick to stem the pangs.(To make matters worse, workers try to satisfy these pangs by consuming more sugary, fatty, processed foods.) On the other hand, when an engaged employee eats a well-balanced meal rich in complex carbohydrates (vegetables and fruits) and (lean) protein, her blood glucose is sustained for about much longer, as illustrated bellow.

The role of oxygen

The brain soaks up at least 20% of the body’s oxygen supply. Remaining sedentary for extended periods (e.g. sitting at a workstation or in meetings for long periods of time) impairs the flow of blood and oxygen — particularly to muscles — which can often lead to fatigue. In fact, research has shown that remaining sedentary for long periods of time can have an independent, deleterious impact on health. What this means is that regular movement can mean the difference between being in an optimal vs. sub-optimal state of health. In contrast to a sedentary body, active bodies need more energy and more oxygen, which is why the breathing rate increases during exercise. Engaging in physical activity can create brief periods of hyperoxygenation in the brain. and increasing oxygen intake has been shown to enhance energy, mental performance and memory recall.Scientists at the University of Illinois found that as little as three hours of brisk walking per week is enough to boost blood flow to the brain and trigger biochemical changes that increase the production of new brain cells.

Exercise improves learning on three levels: it optimizes the mind-set to improve alertness, attention, and motivation; prepares and encourages nerve cells to bind to one another (the cellular basis for logging information); and spurs the development of new nerve cells from the stem cells in the hippocampus. A 2007 study determined that people learn vocabulary words 20% faster following exercise than they did before exercise. “When we get moving,” says researcher and author John Ratey, “exercise naturally stimulates the brain stem and gives us more energy, passion, interest, and motivation. We feel more vigorous”. The role of sleep. Sleep is essential for human recovery. Research has shown significant negative effects associated with insufficient (six hours or less) of sleep per night. These include poor problem- solving and productivity, loss of energy and lower cognition. Without sufficient sleep, employees tend to make more mistakes and suffer more industrial accidents. They are also more likely to develop physical and psychological conditions that may require treatment. In sum, employees can often make cognitive mistakes when they are deprived of the right kind and amounts of food, water, physical activity, and sleep; they perform at their best when provided sufficient levels of each of these critical elements.

Stay tuned for more on the findings from sports science in part 2.

Jack Groppel is the Vice President of Applied Science & Performance Training, Wellness & Prevention, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson company, and Co-Founder of the Human Performance Institute®. He is an internationally recognized authority and pioneer in the science of human performance, and an expert in fitness and nutrition.