We are hard-wired to do better, whether in sport, work, or play (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Individuals and organizations try to be more productive and perform at higher levels; however this is a difficult prospect. What’s more, we are faced with new and powerful changes in the way we work and live. Technology and society have changed faster in the last 50 years than any other time in history. Many of these new elements of life interfere with our ability to meet these challenges by taxing our attention, strength, and stamina. The result is what the Human Performance Institute calls the “human energy crisis,” leading to fatigue, disengagement, judgment errors, stress, and burnout. To address these issues, HPI has created an integrated training model that incorporates behavior change at its core, along with exercise and nutrition components. The foundation for behavior change is grounded in psychological science, translated into an intervention delivered in 1, 2 or 2.5-day immersive trainings, as well as through an Energy for Performance eCourse.

HPI Model

The primary training goal is to improve personal performance and increase quality of life by aligning participants’ direction in life with how and where they spend their energy. The model states that increased life engagement leads to enhanced performance through focusing personal resources on a defined purpose or mission. The intervention is based on two foundational models: 1) the model of human energy called the Energy Management Model and, 2) the change process model.

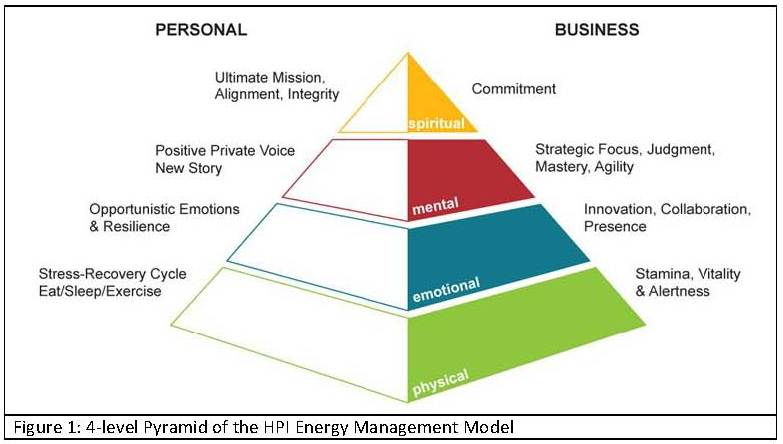

The Energy Management Model includes a four-level pyramid where each level represents a domain of energy. At the top is spiritual, followed by mental, emotional, and physical. The spiritual domain consists of elements that help guide people through their lives. It includes individual purpose, commitment, personal values and principles, and passion. The mental domain consists of focus, awareness, mindfulness, and having effective stories about yourself and your life. Story has been a powerful tool for helping individuals understand themselves and where to go next. The emotional domain consists of elements such as personal confidence, interpersonal effectiveness, and high-energy emotions. For example, high energy can be good, but if energy is high and negative it can quickly damage personal and professional relationships. Last, the physical domain consists of nutrition, fitness, sleep, and recovery, each of which contributes to people’s perceptions of having energy. While nutrition and fitness get the most attention in modern times, sleep is often neglected, and nearly ignored is the important practice of recovery.The HPI model is necessarily broad because it addresses the whole person. As a result, the outcomes cover functioning across mental, physical, social, and emotional health domains, and – perhaps most significantly – vitality (i.e., energy). The implications are also broad, to include helping build healthier and higher-performing individuals in work and in life (e.g. parenting), and enhancing the effectiveness of the organizations to which they belong. Change Process: The change process model consists of three elements 1) Purpose 2) Truth, and 3) Action. Within the training framework, the content is participant-driven, as each individual identifies his or her personal values. The aim is to connect participants with purposes and goals in life that are “intrinsically” motivating, which ensures that there is a natural, inherent reward from pursuit of these goals. This mental realignment often leads individuals to prioritizing the activities that support one’s goal.

Change Process

The change process model consists of three elements 1) Purpose 2) Truth, and 3) Action. HPI trainers refer to identifying one’s purpose in life as finding your “Ultimate Mission.” Trainers facilitate the process of defining a mission, but the end result is entirely determined by the individual. Once a mission, or purpose, has been identified, individuals have an opportunity to confront the trajectory of their lives in light of their mission-based aspirations. Purpose is who I want to be consistent with my deepest values and beliefs and truth is the reality of who I really am. The tension or conflict between these two points of reference can serve as a powerful motivation for change and fuel action. If these are inconsistent, the next step is to acknowledge the “truth” (e.g. discard the old story and write a new, more accurate one) and take action to make the necessary changes. The aim is to align individuals’ lives, thoughts, and actions with their stated purpose (i.e., full engagement). Within the training framework, the content is participant-driven, as each individual identifies his or her personal values. The aim is to connect participants with purposes and goals in life that are “intrinsically” motivating, which ensures that there is a natural, inherent reward from pursuit of these goals (i.e., mission). This realignment often leads individuals to prioritizing the activities that support one’s mission and deprioritizing the activities that don’t. Health improvement is not the primary aim of the program; however, it can become an inherent part of the process.

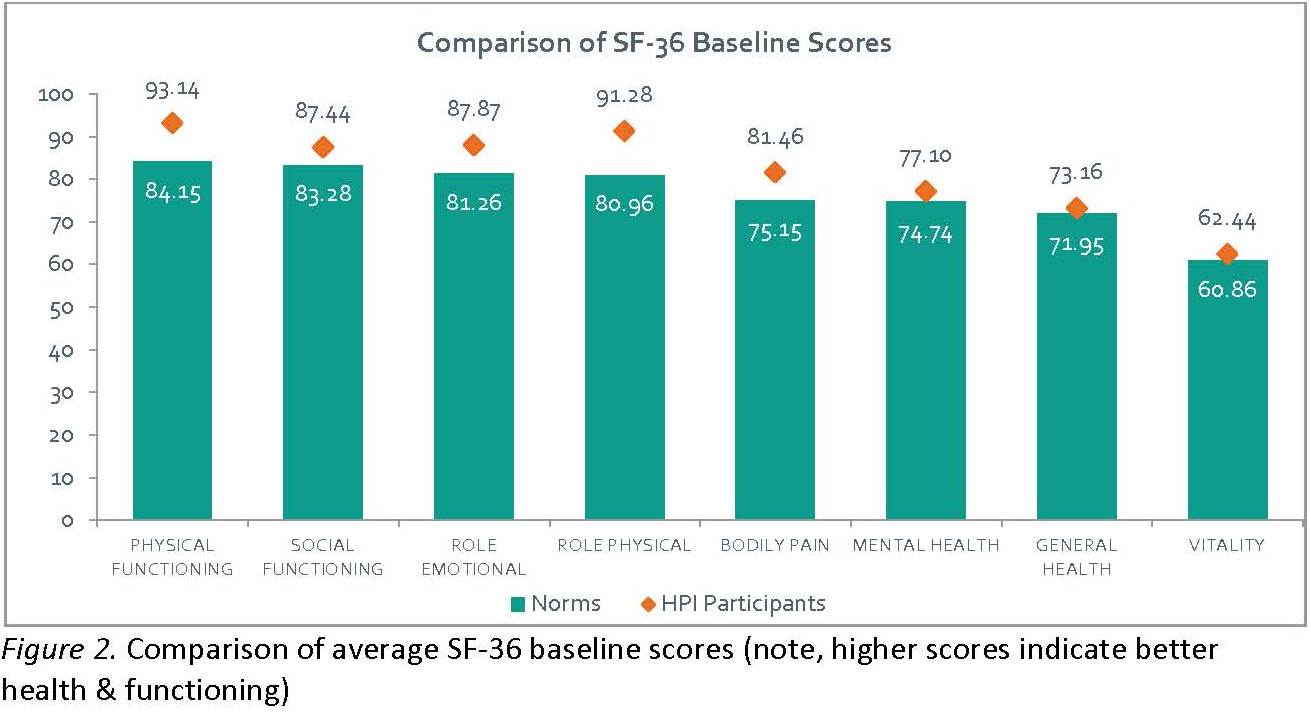

In order to determine the most comprehensive picture of participant data, we collapsed the post-training data across 18 months. As discussed earlier, if the HPI training is effective, energy (i.e., Vitality sub-scale) should show a marked improvement. This was clearly the case, as energy was lowest at baseline, showed the most dramatic improvement, and had the greatest sustained change at 18 months. Similarly, the Mental Health scale improvements suggest that participants experienced meaningful improvements in their emotional lives and well-being. Third among the strongest improvements was General Health, which is the best depiction of how people are feeling across all the domains. To see improvements in this category is particularly impressive, because more global measures of health are usually hard to change (Lee, Jones, Goodman, & Heyman, 2005).The Physical scale also showed improvements initially; however, this was a fairly healthy group at baseline, which limits the potential for score improvement. Last, there are scales such as Bodily Pain that are much less relevant to HPI training. Perhaps most notable, however, is that every scale showed improvement at 6 months. The changes were all sustained over a year, and in some cases through 18 months. These results are fairly dramatic in light of the short duration of the HPI intervention.

Improved Productivity

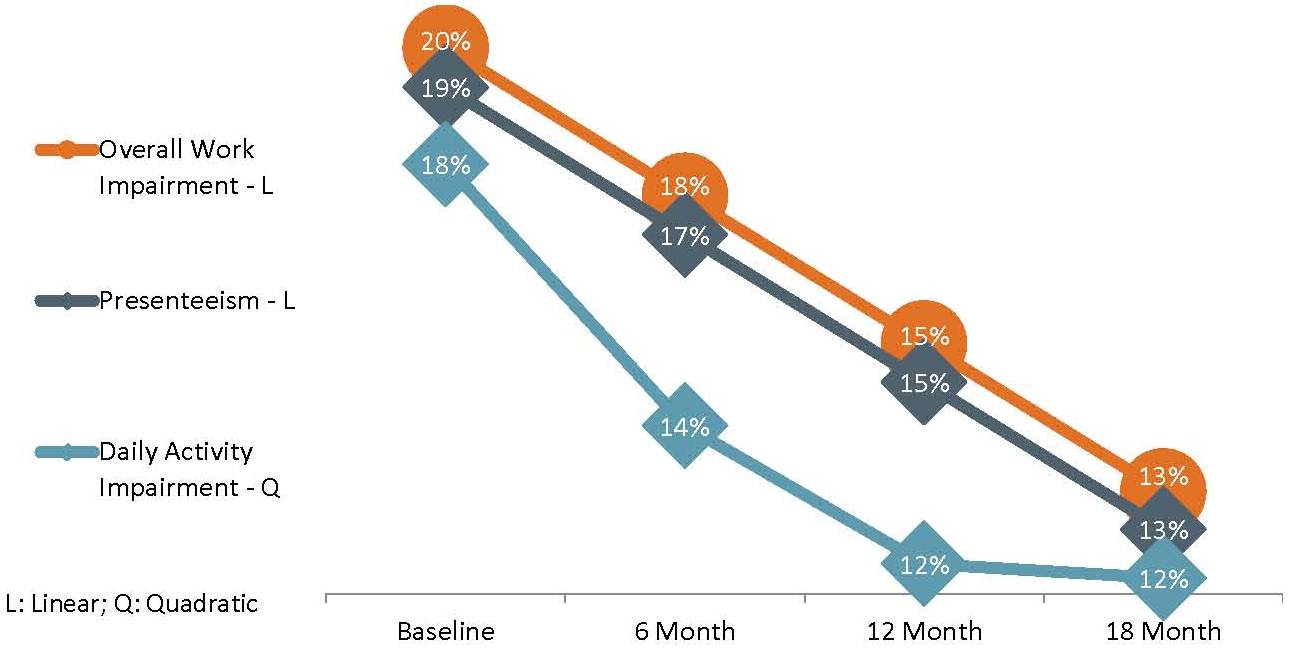

Productivity outcomes were based on the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire (Reilly et al, 1993). The WPAI is a self-report tool designed to assess productivity impairment. The scale contains 6 productivity related questions that measure 1) work-time missed due to health-related and non-health-related issues; 2) the time spent actually working; and 3) the extent to which health is affecting both work productivity and regular daily activities. Here, the WPAI was modified to identify energy as the impairment domain instead of general health problems. Outcomes assessed are based on four subscales from participant responses. In each sub-scale, a higher percentage indicates worse productivity. A brief summary of each sub-scale follows: Absenteeism: a percentage of work time lost due to low energy; Presenteeism: the degree your low energy affects your productivity while you were working; Overall Impairment: a combination of the percentage of work time lost and the working productivity impact due to a low energy related problem; Activity Impairment: the degree to which your low energy affects your ability to do your regular daily activities.

We analyzed the productivity impairment data similar to the method above used for the SF-36. These data were graphed over an 18 month period to demonstrate long-term trends. Most remarkably, overall impairment, daily activity impairment, and presenteeism showed dramatic declines over the 1.5 year period. Overall work impairment and presenteeism had a linear decrease from a baseline of 20% and 19%, respectively, to 13% overall work impairment and 13% overall presenteeism at 18 month follow-up. Daily activity impairment decreased from 18% at baseline to 14% at 6 months, to approximately 12% at 12 month follow-up, with a flattening of change from 12 to 18 month follow-up. Each of these fell approximately 4-7% points over this time. This is important considering that the baseline productivity impairment level is approximately 3.4% in the healthiest populations (Riedel et al., 2009). For absenteeism there was not a significant decrease, but this was not surprising given that the group was relatively healthy.

Improving High Performance Behavior

This study used an employee population and assessed the relationship between Corporate Athlete Training and changes in on-the-job behavior. The organization strategically identified six High Performing Behaviors described below based on their own work (Brandon et al, 2013) and used these as the primary outcomes. Scores were compared between training graduates (n=173) and non-graduates (n=36). In order to minimize group differences, all participants and non-participants were similar in grade and performance levels prior to the study. Non-graduates received the same training as graduates following completion of this study.

Energy management training was developed from work with the most elite athletes and performers. Since then, it has been translated to a broader view of human performance to include the workplace and life roles such as parenting. Our aim here was to capture the accumulating evidence for energy management training and the wide variety of potential applications. The current outcomes capture specific domains such as perceived energy (i.e., vitality), but also include critical general health, and quality of life indicators such as mental, social, physical, and emotional functioning. The evidence shows that helping people to connect management techniques can lead to broad range of positive effects. While energy management training aims to improve the lives of individuals, it also appears to have positive effects on larger social groups or organizations.

There is a continued need for improvement of high performance behaviors and health in corporate settings. In many ways, modern day leaders also need to be exemplars of health to their employees. While employers increasingly rely on monetary incentives to influence health-related behaviors, evidence shows that sustained behavior change happens when people are motivated from within, by what really matters to them (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Jack Groppel is the Vice President of Applied Science & Performance Training, Wellness & Prevention, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson company, and Co-Founder of the Human Performance Institute®. He is an internationally recognized authority and pioneer in the science of human performance, and an expert in fitness and nutrition.